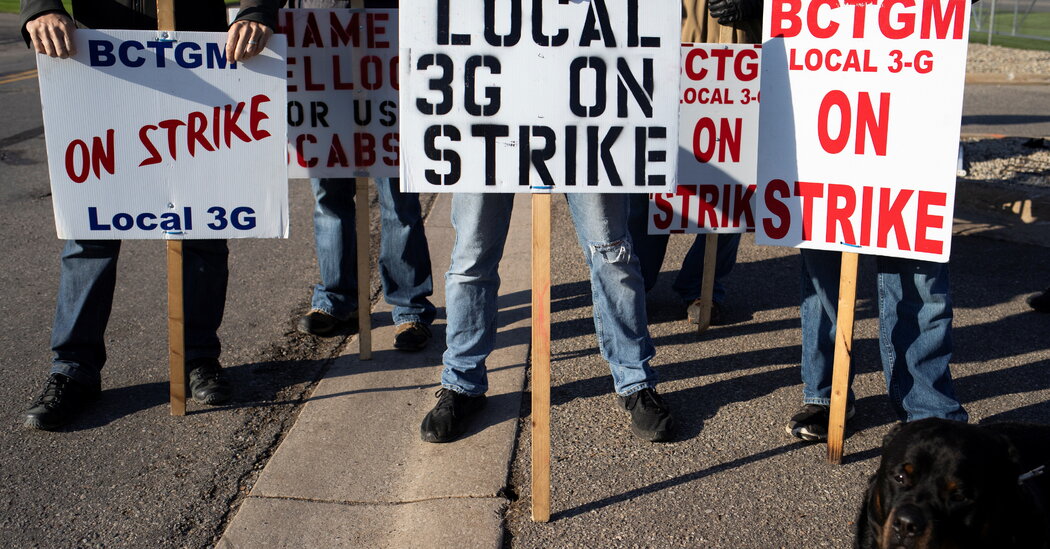

About 1,400 striking workers at four Kellogg cereal plants in the United States have rejected a tentative agreement on a five-year contract negotiated by their union, the company said on Tuesday.

The Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers International Union, which represents the workers, did not reveal the vote totals but said in a statement that its members had “overwhelmingly voted” against the agreement.

The vote was the latest of several recently in which workers expressed dissatisfaction with the terms negotiated by their unions. Deere & Company workers rejected two tentative agreements before approving a third one last month, and some workers there worried that their union was not aggressive enough with the company.

The Kellogg rejection is “similar to what we saw earlier on in Deere,” said Johnnie Kallas, a Ph.D. student at the School of Industrial and Labor Relations at Cornell University and the project director of its Labor Action Tracker. “With the inflation we’re experiencing now and the fact that we’re in a relatively tight labor market, workers do feel emboldened.”

The votes are in keeping with other signs of labor activism. Workers across the economy have grown more assertive in recent months, engaging in strikes and informal actions and taking part in new organizing efforts.

The Kellogg strike began on Oct. 5 and has largely revolved around the company’s two-tier compensation structure, agreed to in 2015, in which newer employees earn lower wages and receive less generous benefits than veteran workers. Under the previous contract, the lower tier could include up to 30 percent of workers.

According to a summary provided by the company, the new agreement would have immediately moved all employees with four or more years at Kellogg into the veteran tier. A group of lower-tier employees, equivalent to 3 percent of a plant’s head count, would move into the veteran tier in each year of the contract.

“We are disappointed that the tentative agreement for a master contract over our four U.S. cereal plants was not ratified by employees,” Kellogg said in a statement.

The company said that no further bargaining sessions were scheduled, and that it would “hire permanent replacement employees in positions vacated by striking workers.”

Permanently replacing workers on strike over economic issues like pay and benefits is legal, though Democrats are seeking to outlaw the practice in the Protecting the Right to Organize Act, or PRO Act. The House passed the bill in March, but it faces long odds in the Senate.

Under the rejected agreement, veteran workers, who Kellogg has said make about $35 an hour on average, would have received a 3 percent wage increase in the first year and cost-of-living adjustments in subsequent years. Newer hires make almost $22 per hour, according to the company.

The company previously proposed eliminating the cap on the percentage of lower-tier workers and setting up a six-year progression to the veteran wage tier. But some employees and union officials saw that as a way to increase the number of lower-tier workers overall. They worried that it could put downward pressure on veteran workers’ wages if those in the lower tier became a majority.

“As soon as the lower tier has 50 plus one, they have voting power on future contracts and my wage can go down,” Dan Osborn, president of a Kellogg workers local in Omaha, said in an interview shortly after the strike began.

Mr. Osborn said at the time that veteran workers at his plant made about $30 per hour and that they felt especially frustrated by the company’s offer after working long hours, often on weekends, during the pandemic. They believed they had leverage over the company because of a general worker shortage and because some of their skills are specialized.

Mr. Osborn said he had fixed and maintained machines at Kellogg for more than 15 years, but added, “There are days, even weeks, when I can’t even get the things going.”

In addition to Mr. Osborn’s plant, Kellogg workers are on strike at plants in Battle Creek, Mich.; Lancaster, Pa.; and Memphis.

The company said in a statement in late November that it was able to “run our plants effectively with hourly and salaried employees, third-party resources and temporary replacements,” and indicated that it was hiring permanent replacement workers.

The strike is part of an increase in labor unrest this fall, including the strike by 10,000 Deere workers and one by more than 2,000 hospital workers in New York, each of which lasted more than one month.

Workers have sometimes directed their frustration at union leaders whom they criticize for not bargaining aggressively enough. Last month, the nearly 1.4 million-member International Brotherhood of Teamsters elected a president who had challenged the candidate backed by the union’s departing president, James P. Hoffa, on the grounds that the union had been too willing to accept concessions under Mr. Hoffa’s leadership.

More than half the roughly 420 workers on strike at a Heaven Hill spirits bottling plant near Louisville, Ky., voted to reject a tentative agreement between their union and the company in late October, but the six-week-long strike could be prolonged only with at least two-thirds opposition under union rules.

“I think there’s a lot of anger,” Mr. Kallas of Cornell said. “It is a unique moment. But what sort of gains that translates into in the long term very much remains to be seen.”