The anti-trade protectionists are again in energy, and so they’re promising as soon as once more to “bring back good-paying jobs” that America supposedly had “stolen” from us through the years as a result of “unfair” overseas competitors. Tariffs are after all the popular software of protectionists previous and current, and President Trump has heralded tariffs as “the most beautiful word in the dictionary.” Howard Lutnick, Trump’s Commerce Secretary and influential financial advisor, articulated very clearly in a current interview that the aim of Trump’s tariffs is to spice up manufacturing employment within the US:

“…under Donald Trump union labor is going to double because those factories are going to come back and those workers are going to get great jobs and we are going to have a different America, one that produces and manufactures. And if I need to use tariffs—this is the president talking—if I need to use tariffs to bring that manufacturing home, we’re going to do it.”

Tariffs and rumors of tariffs are sowing doubt, confusion, and worry about present and future US financial efficiency. It is a disgrace as a result of Trump’s broader financial coverage bundle, that includes deregulation, decrease taxes, low cost and considerable vitality, minimizing authorities waste, and many others., would in any other case be strongly pro-growth. Trump’s tariffs are doing to the economic system what Plaxico Burress did to the NY Giants, and economists are rightfully talking out towards the counter-productive idiocy of Trump’s shoot-from-the-hip, on-again off-again tariff pronouncements.

Others have spoken effectively concerning the financial injury of tariffs. Right here I wish to take a deeper look into the protectionists’ claims about jobs—dropping them and bringing them again. Have we misplaced manufacturing jobs? Sure. Is that this due to commerce? Partly. Is it a nasty factor? Definitely not. Protectionists commit the basic financial fallacy outlined by Frederic Bastiat:

“There is only one difference between a bad economist and a good one: the bad economist confines himself to the visible effect; the good economist takes into account both the effect that can be seen and those effects that must be foreseen.”

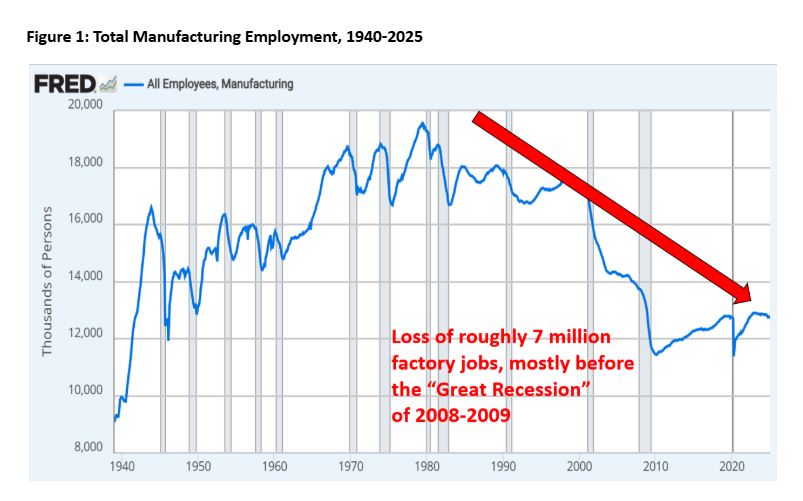

So let’s have a look at the massive image, past the job losses, and assess total modifications within the US economic system throughout this period of alleged manufacturing decline. Happily, information makes it pretty straightforward to see, a minimum of in broad phrases, the job-shifting affect of worldwide commerce. First, we’ll acknowledge the magnitude of the manufacturing job losses. As proven in Determine 1, manufacturing employment within the US dropped by about 1.5 million from pre-Nice Recession ranges (2006), and is down by almost 7 million, or 35%, from the all-time excessive reached in 1979.

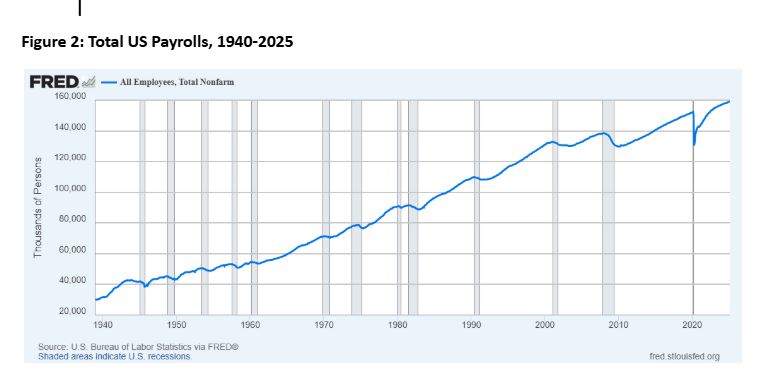

So certainly, the US had been dropping manufacturing jobs for many years, regardless of a small restoration of about 1.5 million from the Nice Recession nadir. The general development provides prima facie help to the demagogues’ arguments about outsourcing and the so-called “de-industrialization” of America. However manufacturing is simply a part of an unlimited US economic system. What can we observe once we have a look at employment in the whole economic system? First, let’s observe that complete employment numbers wax and wane with the enterprise cycle. As an illustration, we skilled a surprising and almost instantaneous payroll drop of twenty-two million throughout the Covid shutdowns of early 2020. These losses have been absolutely recovered inside two years, although, and since mid-2022 the US economic system has been including jobs on a comparatively regular foundation. Payroll employment hit a brand new all-time excessive of 159 million as of the February 2025 jobs report. The primary factor to be noticed is the regular and positive long-run uptrend in complete jobs, as seen in Determine 2.

Not solely are jobs rising, however job progress has outpaced inhabitants progress—i.e. the rise within the variety of individuals obtainable to fill these jobs—and this has been the case for many of the final 4 many years, as seen in Determine 3.

In my subsequent publish, I’ll flip will flip to the query, “Is the fact that more people are working good news for the economy?”

Tyler Watts is a professor of economics and administration at Ferris State College.