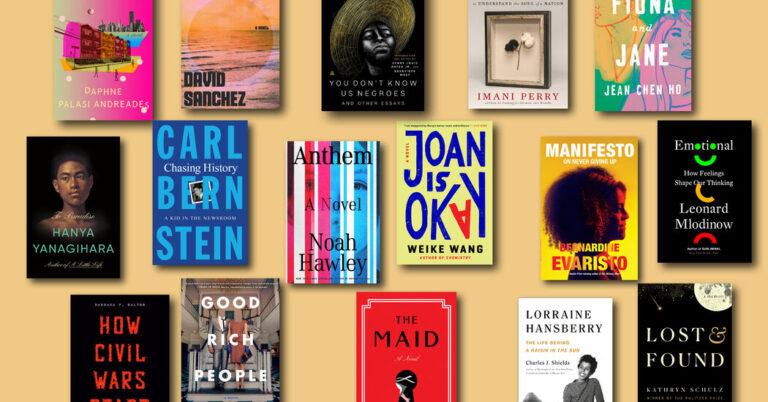

‘All Day Is a Long Time,’ by David Sanchez (Mariner, Jan. 18)

This coming-of-age debut follows David, a teenager on Florida’s Gulf Coast, as he battles drug addiction, dips in and out of jail and eventually, falls back on his love of reading to find solid ground.

‘Anthem,’ by Noah Hawley (Grand Central, Jan. 4)

A cast of teenagers defend against a number of adversaries — from a widespread mental health crisis years after the outset of the coronavirus pandemic to a malevolent man resembling Jeffrey Epstein — in this new thriller from Hawley, known for his work on TV series such as “Bones” and “Fargo.”

‘Brown Girls,’ by Daphne Palasi Andreades (Random House, Jan. 4)

In Queens, a group of young friends — who describe themselves as “the color of 7-Eleven root beer,” “the color of sand at Rockaway Beach when it blisters the bottoms of our feet” and the color of soil” — make their way in New York and beyond.

Bernstein begins his memoir in 1960, when he landed his first job in journalism: as a copy boy at The Washington Star. Bernstein chronicled many of the country’s most riveting stories even before he broke news of Nixon’s Watergate crimes, and he recounts his experiences with a mix of wonder and pride.

Rationality, reason and logic have been heralded as the foundation of a clear mind, but Mlodinow, a physicist, argues that taking our feelings into account can help us make better decisions. He offers plenty of real-world examples, including his parents’ experiences as Holocaust survivors.

‘Fiona and Jane,’ by Jean Chen Ho (Viking, Jan. 4)

This debut story collection centers on two Taiwanese Americans growing up in Los Angeles as they explore class, sexuality, friendship and family secrets — and, later, how to sustain their friendship through the ups and downs of young adulthood.

‘Good Rich People,’ by Eliza Jane Brazier (Berkley, Jan. 25)

In this new thriller, a case of mistaken identity places Demi in the cross hairs of a wealthy couple, Lyla and Graham, who have devised a sinister game that plays out at their Hollywood Hills mansion.

A political scientist outlines the reasons the United States may be on the brink of another violent civil conflict.

‘Joan Is Okay,’ by Weike Wang (Random House, Jan. 18)

Joan, an I.C.U. doctor at a New York City hospital, fends off suggestions from her sister-in-law that she’s not a real woman without children of her own, while mourning her father and dealing with her widowed mother. She’s solitary, literal-minded and extremely awkward — all of which contribute to the hilarity of this novel.

Hansberry is best remembered for her acclaimed play “A Raisin in the Sun,” the first by a Black woman to be performed on Broadway. “Never before, in the entire history of the American theater, had so much of the truth of Black people’s lives been seen on the stage,” James Baldwin wrote. Shields, the biographer of Harper Lee and Kurt Vonnegut, draws on correspondence, interviews and more as he delves into Hansberry’s upbringing, politics and sexuality.

The Pulitzer Prize-winning writer reflects on meeting her spouse and the death of her father as she examines the role that discovery and loss play throughout everyone’s lives, from the large scale (wars, displacement, pandemics) to the intimate (hunting around the house for a misplaced trinket).

‘The Maid,’ by Nita Prose (Ballantine, Jan. 4)

In Prose’s charming, eccentric debut, Molly — who struggles with social skills and cues — takes pleasure in her solitary job cleaning rooms at the Regency Grand Hotel until she finds herself a suspect in a guest’s murder.

‘Manifesto,’ by Bernardine Evaristo (Grove, Jan. 18)

In this memoir, Evaristo, the first Black woman to win the Booker Prize, reflects on her decades-long career.

‘To Paradise,’ by Hanya Yanagihara (Doubleday, Jan. 11)

Yanagihara, the editor of T Magazine and the author of “A Little Life,” imagines alternate Americas, the first in 1893, when the country consists, post-Civil War, of separate territories; another in 1993, when a Hawaiian man living in New York reckons with his past as the city confronts H.I.V.; and the third in 2093, when America is beset by pandemics and authoritarian rule.

Perry, a professor of African American studies at Princeton and an Alabamian, argues that to understand the full history of America, one must study the South. Examining the region, she writes, “allows us to understand much more about our nation, and about how our people, land, and commerce work in relation to one another, often cruelly, and about how our tastes and ways flow from our habits.”

‘You Don’t Know Us Negroes: And Other Essays,’ by Zora Neale Hurston. Introduction and edited by Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Genevieve West. (Amistad, Jan. 18)

The first comprehensive anthology of Hurston’s nonfiction brings together previously published and new work, touching on everything from jazz to school integration.