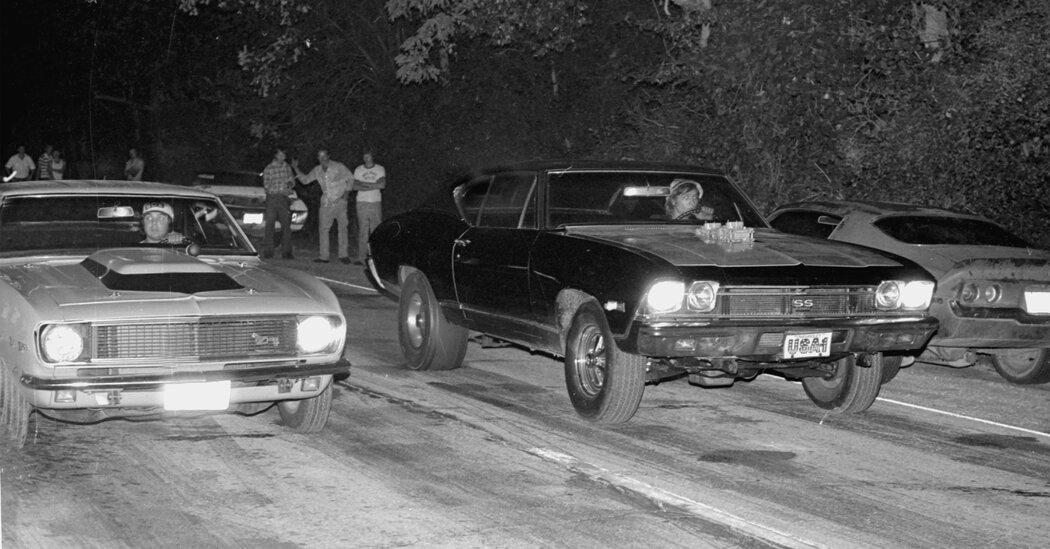

Long after sundown one day 44 years ago, 21-year-old Kevin Lawrence stepped out of his ’68 Chevelle onto a sparsely traveled road just beyond Chicago’s suburban sprawl. After hushed negotiations with another young man, he settled into his car and ignited an engine that barked powerfully before settling into a bass-beat idle. He switched on the headlights, illuminating 50 feet of road. I jabbed at the shutter of a beat-up camera, clicking off frames as my flash defied the darkness.

Mr. Lawrence — a fishing hat atop his head — was intently focused on the road ahead. To his right was a Camaro with huge rear racing slicks. A few dozen young people were gathered on the roadside; among them was his wife and racing partner, Pam Pappas Lawrence.

A raised hand fell, and both cars screamed off into the darkness, accelerating to 120 miles an hour in 12 seconds just as flashing police lights rushed in from behind. The spectators jumped into their cars and followed the racers. I did likewise. A few stragglers were pulled over and subsequently released after insisting they didn’t know the offenders.

Earlier that night, dozens of teenagers and 20-somethings had gathered at Duke’s Drive-In in Bridgeview, just outside Chicago, to show off their hopped-up cars and perhaps earn some cash in contests of acceleration on the street. On that August 1977 evening, the crowd was large, with outrageous machinery occupying every available space and spilling onto Harlem Avenue. The group had heard that an aspiring journalist would be on hand, documenting the drive-in’s reputation as a hotbed of illegal street racing for “Hi-Performance CARS,” a long-gone magazine that targeted the outlaw fringes of the hot-rod hobby.

Cars were an obsession for many at that place and time. Social media and the internet weren’t even on the horizon. The athletes stayed busy with sports, but for many others there were cars. Teenagers of all stripes spent their free time under the hood, busting knuckles to make their car drivable. Once it could move under its own power, they would work harder still to make it faster. And hopefully the fastest.

Mr. Lawrence, now 65 and living in Palos Hills, Ill., was among the fastest at the drive-in that night. He was an automotive veteran. At 12 he had tagged along with an uncle who worked at a body shop. There, he swept the floor and went along on tows. Soon he learned to repair crumpled cars. But he was intrigued by the mechanical side of things, so his uncle taught him to rebuild engines.

They built a modified car — a Ford Starliner with a hopped-up V-8 — and it performed better than most muscle cars on occasional drag strip runs. But a day at the track was a major undertaking. After an early rise there was the 45-mile trip to the U.S. 30 drag strip in Merrillville, Ind., where there were entry fees and long hours waiting in line to make two or three runs over a 10-hour day.

After high school, Mr. Lawrence was hired by P&G Engineering, a shop owned by a local pro racer. He furthered his automotive education, as he rebuilt carburetors, performed tuneups and ran a dynamometer that measured the rear-wheel horsepower of customers’ cars.

Access to the dyno and the other resources at P&G proved invaluable as Mr. Lawrence was building a hot rod of his own — the 1968 Chevelle SS. The original 396-cubic-inch V-8 gave way to a 454-incher with dual four-barrel carbs.

With more than 500 horses on tap, it was quick. The dyno confirmed its potential, and Duke’s helped Mr. Lawrence put it to the test, often with substantial sums on the line. The drive-in provided camaraderie as well.

“The guys and gals who hung out at Duke’s watched out for each other,” Mr. Lawrence said. “We competed, but we were friends, and when unknowns showed up looking for a race, we took them on.”

After the photo of Mr. Lawrence and his street-racing Chevelle appeared in the magazine, racers from metro Chicago and beyond traveled to Duke’s to challenge him and others, who proudly wore jackets emblazoned with “Duke’s Drive In, home of thee fastest street cars.”

Mr. Lawrence competed on the street for more than 10 years — winning about 90 percent of his races and developing a reputation as a guy to beat if you wanted to make a name for yourself among Chicago’s street racing fraternity. He still worked days as a mechanic, but the race winnings helped make life better for the Lawrences’ growing family, which now included two daughters, Danielle and Nicole — both of whom would eventually see success behind the wheel of race cars.

Mr. Lawrence was pulled over numerous times while racing. “The officer usually gave me a variety of tickets,” he said. “I once decided to contest a ticket for 125 miles per hour in a 50-mile-per-hour zone. The judge called me into his chamber and said in so many words: ‘You don’t want to do this. Pay the ticket and be quiet.’ I followed his advice that day and thereafter.”

“I made enough money street racing to put together a down payment on my house,” he said. “Then I called it quits.”

“I kind of grew up,” Mr. Lawrence added. “At one time, street racing, as we practiced it on the Southwest side of suburban Chicago, was relatively safe. We raced on rural roads devoid of houses and businesses, and we closed the road to what little traffic there was. But eventually there was more development in our area, which brought in more traffic. What’s more, street racing was illegal. As my girls reached school age, I wanted them to understand that breaking the law has consequences.”

But Mr. Lawrence didn’t lose either his love of automobiles or his desire to compete, so he teamed up with his buddy Scott Fulkerson on a National Hot Rod Association Pro Stock car.

Pro Stock drag racing cars look like passenger cars, but they’re sophisticated race cars with an exactingly engineered tube chassis under the body and a highly modified drivetrain. Capable of accelerating to 200 m.p.h. in seven seconds, they have virtually nothing in common with the production cars they resemble.

Jumping from the street to Pro Stock — the most competitive class of N.H.R.A. drag racing — was a formidable challenge. In the 1990s, when Mr. Lawrence and Mr. Fulkerson leaped into the fray, the fasted and slowest cars in the fields of 16 were often separated by just a tenth of a second. And it wasn’t uncommon for as many as 40 well-financed cars to compete for those 16 spots.

Unlike its big-dollar competitors, the fledgling team operated out of the garage behind Mr. Lawrence’s house, just as he had in his street-racing days. Ms. Lawrence, who had always been her husband’s right-hand woman, pitched in, and soon their two daughters were lending a hand as well.

In 1997, Mr. Fulkerson married, and racing wasn’t part of the plan. That made finances even tougher. The competition was spending thousands a week on research and equipment. Mr. Lawrence was trying to compete on a small fraction of that.

He recalls that 36 cars vied to qualify for a 16-car field at Memphis. The 16th qualifier covered a quarter-mile in 6.803 seconds. Mr. Lawrence was No. 21 at 6.806.

Finally, in his last two years racing, he qualified his Pro Stock Chevrolet Cobalt for an event. His pit crew, now with over a dozen friends and relatives, erupted. Tears of joy were shed. He would go on to qualify again, but his tank was nearing empty.

“I tried and tried,” Mr. Lawrence said, but he was exhausted. Facing better-funded teams, he added, “I bailed and sold everything.”

But that wasn’t the end: Enter nostalgia racing — a brand of quarter-mile competition featuring facsimiles of great cars of years past, raced for a guaranteed fee at booked-in shows. Mr. Lawrence built a near-perfect reproduction of one of the most famous Pro Stock cars of all time, Warren Johnson’s Oldsmobile Cutlass. Mr. Johnson was one of the N.H.R.A.’s winningest drivers for many years. He and his wife, Arlene, contributed technical advice, team uniforms, decals and more.

In shakedown runs, the car recorded 6.8-second quarter-mile times at over 200 m.p.h. That’s virtually unheard-of for a new car and testimony to the fruits of Mr. Lawrence’s 40-plus years of racing experience and the expert help he gets from his family.

“I’ll run five or six nostalgia Pro Stock shows with the Cutlass this year, but it will be a family affair,” Mr. Lawrence said. “My daughters are busy moms, so they no longer race, but they are part of my crew and are training the next generation of Lawrence family drivers.”

At many events, Mr. Lawrence’s grandchildren, including 10-year-old Katelyn, 9-year-old Johnny and 8-year-old Sydney, will drive Lawrence-family-built junior dragsters — essentially, go-karts that look like dragsters.

It’s in their blood.